The Holy Mountain (1973) (dir. Alejandro Jodorowsky)

“These withered hands have dug for a dream, sifted through sand and leftover nightmares” - Beck, “We Live Again.”

Alejandro Jodorowsky’s The Holy Mountain is one of cinema’s most daring works—defying categorization yet demanding your attention. A mix of spiritual odyssey, political satire, psychedelic fever dream, it epitomizes counterculture cinema and remains as provocative and enigmatic today as it was nearly five decades ago. I’ve never seen anything like it and that’s precisely what I hope to discover in life when it comes to this complicated journey through a wide-eyed passion for the arts in attempt to understand why human beings are so inherently fucked up yet sometimes capable of creating something like this.

After moving from Paris to Mexico City in 1960, Jodorowsky’s interest in surrealist art led to the Panic Movement—an art collective co-founded in France in 1962 with Fernando Arrabal and Roland Topor. Named after the god Pan and influenced by Luis Buñuel (another favorite of mine) and Antonin Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty, it aimed to transcend surrealism’s boundaries. The movement sought to disrupt artistic norms through absurdist, avant-garde, and surrealist methods, influencing performance art, short films, experimental expressionism.

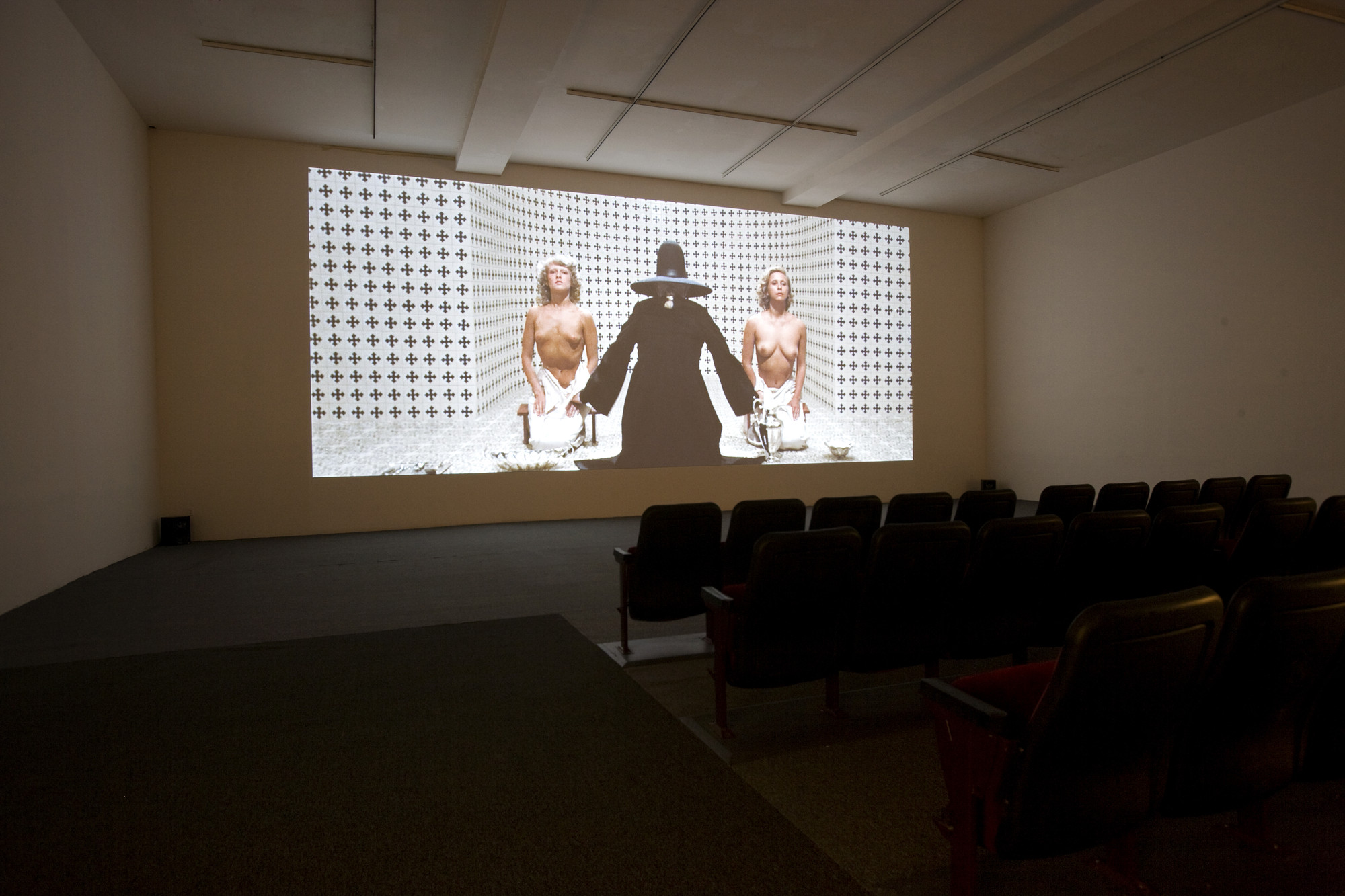

Central to Jodorowsky’s approach is his deep connection to Antonin Artaud’s “alchemical theater.” Jodorowsky called Artaud’s “The Theater and Its Double” his “bible” and was inspired by Artaud’s travels to Mexico. Artaud’s Theater of Cruelty aimed to abandon texts and language, using a visual language of violent, humorous symbols to impact the spectator’s unconscious and provoke a shattering of normative reality through psychic excitation.

As Artaud wrote in “The Alchemical Theatre…”

“There is a mysterious identity of essence between the principle of the theater and that of alchemy... aiming on the spiritual and imaginary level at an efficacy analogous to the process which in the physical world actually turns all matter into gold.”

Jodorowsky echoes these sentiments when he claims that his films are densely layered with symbols (particularly symbols of the Tarot) to activate universal symbols within the viewer’s unconscious. His mysticism, like Artaud’s “alchemical theater,” seeks an “objective art” that speaks to a Jungian collective unconscious - something that speaks to me on a profound level. The more that a film reflects a dreamscape, the more I’m likely to love it.

Produced by Beatles manager Allen Klein and partly funded by John Lennon and Yoko Ono with a $750,000 budget, the film offered unprecedented artistic freedom. As instructed by a Buddhist teacher, Jodorowsky and his wife abstained from sleep for a week before production.

They created a microcosm where their practices mirrored the film’s visuals, embodying art imitating life. The film mimics an acid trip for enlightenment, reflecting communal experiences before its creation. Clearly, hallucinogens of many kinds significantly influenced Jodorowsky and his cast. The crux of the story follows the metaphysical thrust of Mount Analogue.

We meet The Thief, a Christ-like figure who awakens in the desert, his face covered in flies. Befriending a dwarf with severed limbs, they entertain city locals. The Thief’s resemblance to Jesus leads to making plaster Christ copies for tourists, critiquing religious commercialization.

This act critiques contemporary society, highlighting humanity’s deviancy and self-destructive path. It reflects a rejection of materialism, shedding vanity derived from fear, hedonism, identity, class, and self-image.

The film challenges institutions and relationships with death, greed, and power. It uses oppressive regimes, Nazi imagery, and colonial references to expose our attitudes toward the cult of personality, parasitic voyeurism, cultural destruction, and religious commercialization.

The second act begins when the Thief scales a tall tower to find the source of the gold dropped to the people below. At the top, he meets the Alchemist (played by Jodorowsky), who accepts the Thief as his apprentice, stating, “You are excrement. You can change yourself into gold.” I couldn’t help but think of “We Live Again,” by Beck and how this process can blow your “soul crazy.”

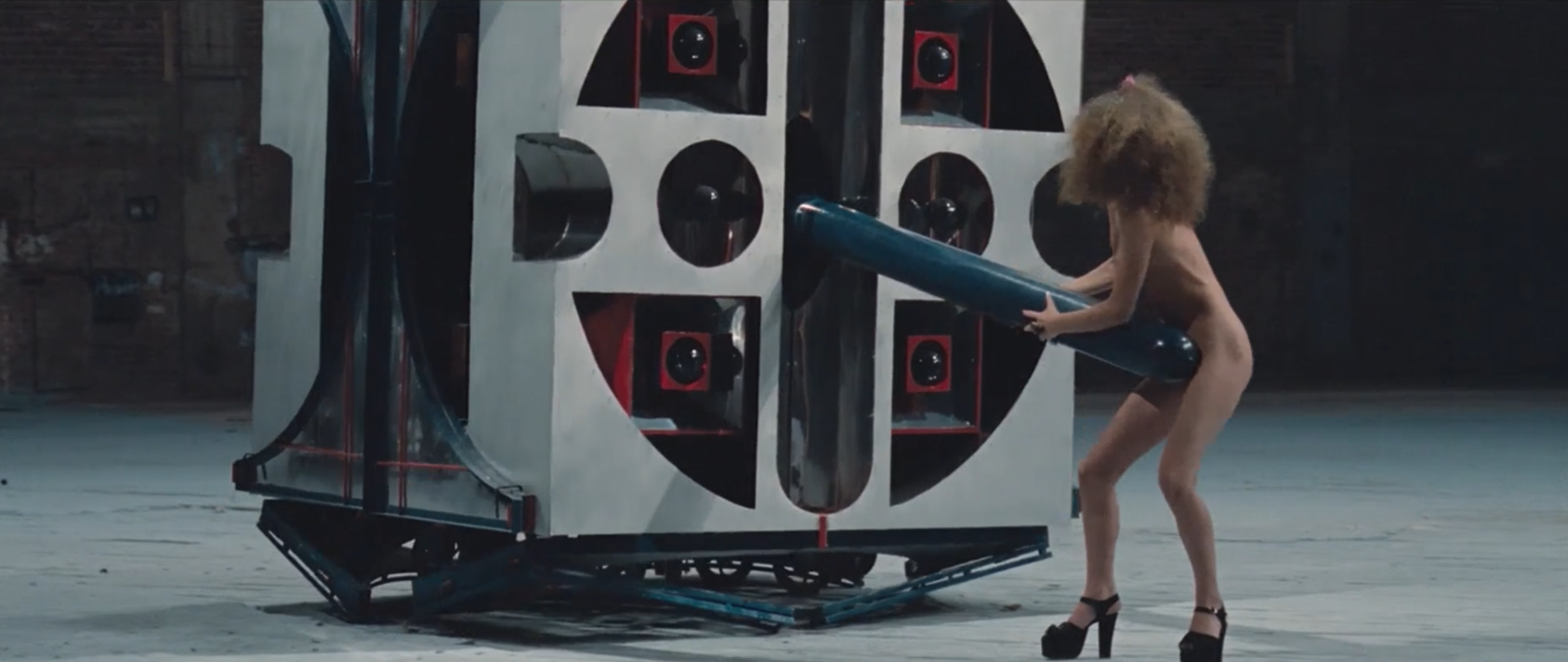

The Alchemist introduces seven others joining their quest, each representing a planet and achieving fame through nefarious means. These disciples embody society’s corruption:

- Fon, a manufacturer of artificial body parts to “enhance” people’s beauty

- Isla, a weapons manufacturer who makes weapons stylish and irresistible to the public

- Sel, a creator of violent toys

- Axon, a merciless warmonger

- Plus, a corrupt advisor, a superficial art dealer, and a hedonistic architect

This part of the film shows archetypes needing a sense of deeper connection. Each disciple, disillusioned with their world, seeks higher knowledge and purpose. The Alchemist ceremoniously cleanses them, having them burn their money and wax images of themselves.

The final act follows the group’s pilgrimage to the Holy Mountain, seeking immortality and to overthrow the eight immortal gods. They face obstacles like the Pantheon Bar, fears of death, intense sexual violence, representing the barriers to actualization.

Through rigorous physical and spiritual discipline, each disciple sheds layers of their past selves. As they ascend the Holy Mountain, each overcomes their greatest fears and learns to exist outside of the physical vessel of their bodies. Just before reaching the summit, the Alchemist urges the Thief to return home—a surprising turn that denies the most sympathetic character enlightenment after all he’s endured. On the summit, the followers attempt to overtake the gods, only to find mannequins—there are no gods.

The Alchemist gathers his subjects, looks into the camera, and commands, “Zoom back, camera!” to reveal a film crew. “We began in a fairy tale and we came to life, but is this life reality? No. It is a film. Zoom back, camera. We are images, dreams, photographs. We must not stay here. Prisoners! We shall break the illusion. This is magic! Goodbye to the Holy Mountain. Real life awaits us.”

This ending breaks the fourth wall, with Jodorowsky, as the Alchemist, addressing both his followers and the audience. Those seeking enlightenment find nothing—no immortal gods, no Holy Mountain, no secret to happiness. Only reality awaits. God forbid! Also, how freeing!

True enlightenment cannot be found through external quests or gurus, but must come from within and must be applied to real life. For someone who finds enlightenment through the arts, as a way to cope with reality, the ending solidified precisely why I adore audacious cinema like this that takes risks. I had no idea what image was going to appear before my eyes next.

Jodorowsky crafted a layered, ambitious spectacle where each frame unveils new concepts through extraordinary cinematography and an enigmatic narrative, blending fragmentation and cohesion. The film’s droning sound design, mixing ambiance with spiritual, cosmic rituals, transports us to otherworldly transcendence; a beautifully orchestrated phantasmagorical opera.

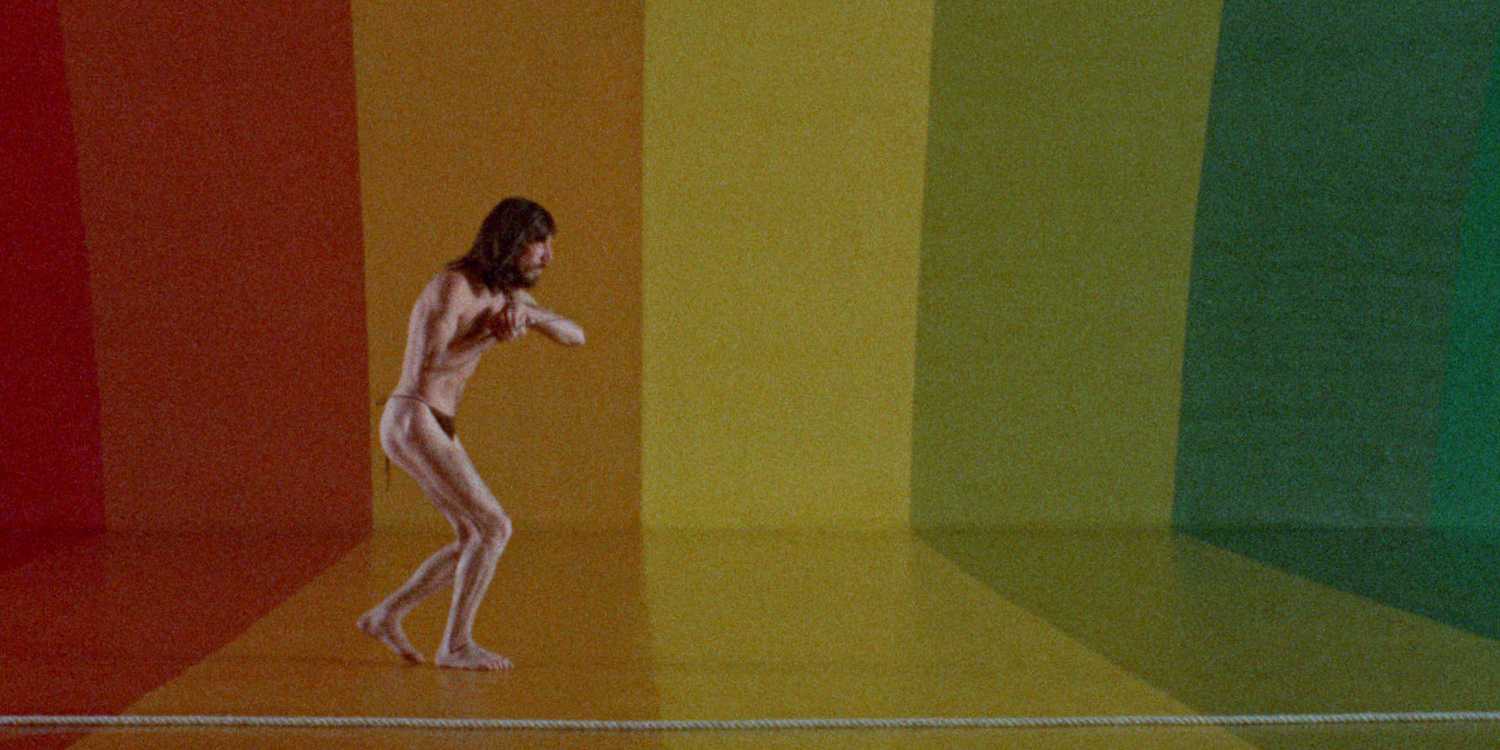

Almost every shot holds double meanings and thematic layers to where I can’t wait to watch this again. Superlatively weird images abound—a creepy old man gifting his glass eye to a child prostitute; a woman told to “rub your clitoris against the mountain”; an army of lizards battling frogs, each in costume. There are so many moments that are hard to describe because a lot happen so quickly.

Beyond spiritual layers, The Holy Mountain is a scathing political critique that still hits home. Jodorowsky’s vision of a broken society reveals mankind’s worst traits. Masked soldiers shoot civilians as tourists snap photos (not much has changed). Religion and sex are commodified. Humans are both vile and incredible. There’s nothing we can do to stop how pleasure intermingles with pain or how capitalism will ultimately kiss the forehead of an innocent child.

The film’s core message reflects mankind’s corruption and the rapture in life’s simple pleasures. Yes there is death and disease, but there is also life experience (as reflected through surrealism here) that allows you to forget the fact that existence is fleeting or that your body is slowly in a state of decay. Jodorowsky portrays overcoming human vices through self-discipline while critiquing systems perpetuating suffering.

The Holy Mountain occupies another time and space, finding its own language and fractured reality that doesn’t always makes sense. It spurs conversations and ideas individually and collectively that become part of broader musings on the nature of existence. I have a feeling I will be coming back to this film again in the near future and having a lot more to say (it’s almost inevitable).

This is a hallucinatory dream masquerading as cinema, and much like psilocybin, somehow he tapped into something beyond the realm of mere collective consciousness. There’s more than meets the eye, the mind, the heart, the blood. How can one even begin to parse what everything could ultimately mean or represent? Perhaps you should just let it unfold, take it in like you’re being seduced, don’t think too much.

Any artistic statement that challenges viewers to broaden their perspective with enlightenment rather than archaic turbulence or dominance is worth celebrating now more than ever. If only the idiots in power knew or could comprehend what a film like this is trying to say. Perhaps we should tie them down (Clockwork Orange-style), give them mushrooms and force them to watch something that is essentially saying, “you are living life the wrong way.”

In an era of increasingly homogenized desires of control, The Holy Mountain is out of control, standing as a reminder of cinema’s potential to provoke, challenge, and transform—not merely through content, but through its lack of convention and the demands it places upon its audience. In other words, movies can be whatever they want to be and there’s nothing you can do to stop it. Let it happen before you, take it all into your mind and most importantly, let love in. Life is too short, death comes quickly… be sure to give yourself moments that involve watching a film like The Holy Mountain before it’s too late.