New Reviews & Mental Filmness Wrap-Up!

Unbanked (2025)

(dirs. David Kuhn, Lauren Sieckmann)

In an era defined by economic uncertainty, soaring inflation, and deepening mistrust of traditional financial institutions, the question of who truly controls our money has never felt more urgent. Unbanked, a new documentary from directors David Kuhn and Lauren Sieckmann, tackles this question head-on through an exploration of Bitcoin and the current cryptocurrency revolution that has captivated—and divided—the world since 2008.

The film begins with a striking image that immediately signals its populist intentions: a man driving his truck through city streets, collecting recyclables and operating as a middleman for those looking to sell their materials—all while seeking payment in cryptocurrency. A Harlem-based can collector becomes an unlikely ambassador for the digital currency movement, embodying the documentary’s central thesis that Bitcoin represents financial liberation for ordinary people.

It’s an opening sequence that grounds what could have been an abstract, technical subject in human terms, showing us that this isn’t just about technology or speculation—it’s about real people seeking alternatives to a system they feel has failed them. At one point, a bank is described as being just a “glorified bookkeeper.”

From this intimate starting point while expanding into perspectives from experts, Kuhn and Sieckmann expand their lens dramatically, taking viewers on a globe-spanning investigation that covers the United States, Argentina, London, Portugal, Costa Rica, Patagonia, Nigeria, and Ghana. The ambitious scope reinforces the film’s argument that financial systems—and their inequities—affect everyone, everywhere. The production values are impressive, with panoramic shots of mining centers, unexpected visual metaphors (including people walking on wire), and fast-paced editing that mirrors the rapid movement of global capital in a digital age.

Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey, Arthur Hayes, Brian Brooks, Nic Carter, Peter Schiff, Erik Voorhees, and Sigal Mandelker all contribute their perspectives, creating a lively debate about the risks, promises, and ethics of digital currency. Downside: Ted Cruz also shows up, ick. Drawing from approximately 60 respondents and 250 hours of footage shot over 15 months beginning in February 2022, the directors have crafted what amounts to a comprehensive primer on cryptocurrency’s impact on global finance.

Overall this exploration excels at making complex financial concepts accessible to general audiences. It revisits the mythology surrounding Bitcoin’s mysterious creator, Satoshi Nakamoto, and carefully explains the mechanics of mining, blockchain technology, and the intricate systems that sustain this decentralized network.

Presented are fundamental questions about the history of currency, the mechanisms of monetary control, and what decentralization could mean for the lower and working classes. For viewers with little understanding of cryptocurrency, Unbanked serves as an entertaining educational tool, unfolding as a journey of discovery that mirrors the filmmakers’ own learning process. Though in terms of execution, it’s fairly conventional with interviews, talking heads and various ideas provided from historical context.

As the directors explain in their statement, they began filming with very little understanding of Bitcoin—on purpose. “At its best, documentary filmmaking is a journey of discovery,” David Kuhn notes, “and I wanted to ‘learn the subject matter by doing’ and let the process unfold on film.” This approach gives the documentary an accessible, exploratory quality that invites viewers to learn alongside the filmmakers rather than feeling lectured to by experts. This is not Margot Robbie preaching to the camera from a bathtub in something like The Big Short. There’s no talking down; there’s a lot of ideas being presented in a way that does provide food for thought. Even if I didn’t comprehend it all and it’s quite biased, I was still mostly engaged and interested.

The coverage of devaluation in Argentina and Nigeria serves as vivid case studies, illustrating how volatile economies and failing currencies push ordinary citizens toward cryptocurrency as a means of survival and defiance. These sequences underscore the social justice dimensions of Bitcoin’s appeal, showing how people in economically unstable regions view digital currency not as speculation but as a lifeline—a way to preserve their wealth when their national currencies are collapsing around them.

A cross-section of risk-takers, rebel makers, revolutionaries, wealth-seekers, dreamers, and the so-called “little guy,” emphasize that the cryptocurrency movement encompasses people from all walks of life and ideological backgrounds. This diversity of perspectives helps the film transcend simple partisan politics, presenting Bitcoin as a phenomenon that defies easy categorization along traditional left-right lines.

While the filmmakers have included contrasting opinions and acknowledge concerns about cryptocurrency’s use in criminal activity and warnings from veteran investors like Warren Buffett, the overall tone leans unmistakably toward advocacy. The polished cinematography, the emphasis on empowerment narratives, and the selection of voices create what often feels like an extended commercial for the Bitcoin ecosystem rather than a truly balanced, unbiased investigation.

The documentary also raises questions it doesn’t fully answer. Is a peer-to-peer money system truly practical or sustainable in the long term? What happens when the idealism of decentralization meets the reality of market manipulation, (and much like AI) environmental concerns about energy-intensive consumption, and the potential for new forms of inequality? Sure, the film asks what is valuable in our modern society but it doesn’t really let us sit with the possibility of what is best for society. While the film gestures toward various complexities and complications, it doesn’t always dig as deeply into the contradictions and challenges as some viewers might hope.

Despite this, Unbanked succeeds as both an educational tool and a cultural documentation of our moment. Money, gold-bars, debt - a lot of the way finances exist often allude and confuse. Well, what if it all went digital? The film captures the zeitgeist of an era when traditional financial institutions face unprecedented skepticism, when generational wealth gaps continue to widen, and when people around the world are actively seeking alternatives to systems they perceive as rigged against them. Whether Bitcoin represents genuine liberation or simply a new form of financial faith remains an open question—one that the documentary invites viewers to grapple with themselves.

Unbanked works best as an entry point into the cryptocurrency conversation—a well-crafted infomercial-like documentary that makes a complex subject comprehensible and human. While those seeking a more critical or balanced examination of Bitcoin’s drawbacks may want more in-depth analysis, viewers looking to understand why millions of people worldwide have embraced digital currency will find much to appreciate. In a financial landscape increasingly defined by uncertainty and disruption, Unbanked offers a compelling, if somewhat one-sided and simplified, glimpse into what might be the future of money—or might be just another bubble waiting to burst.

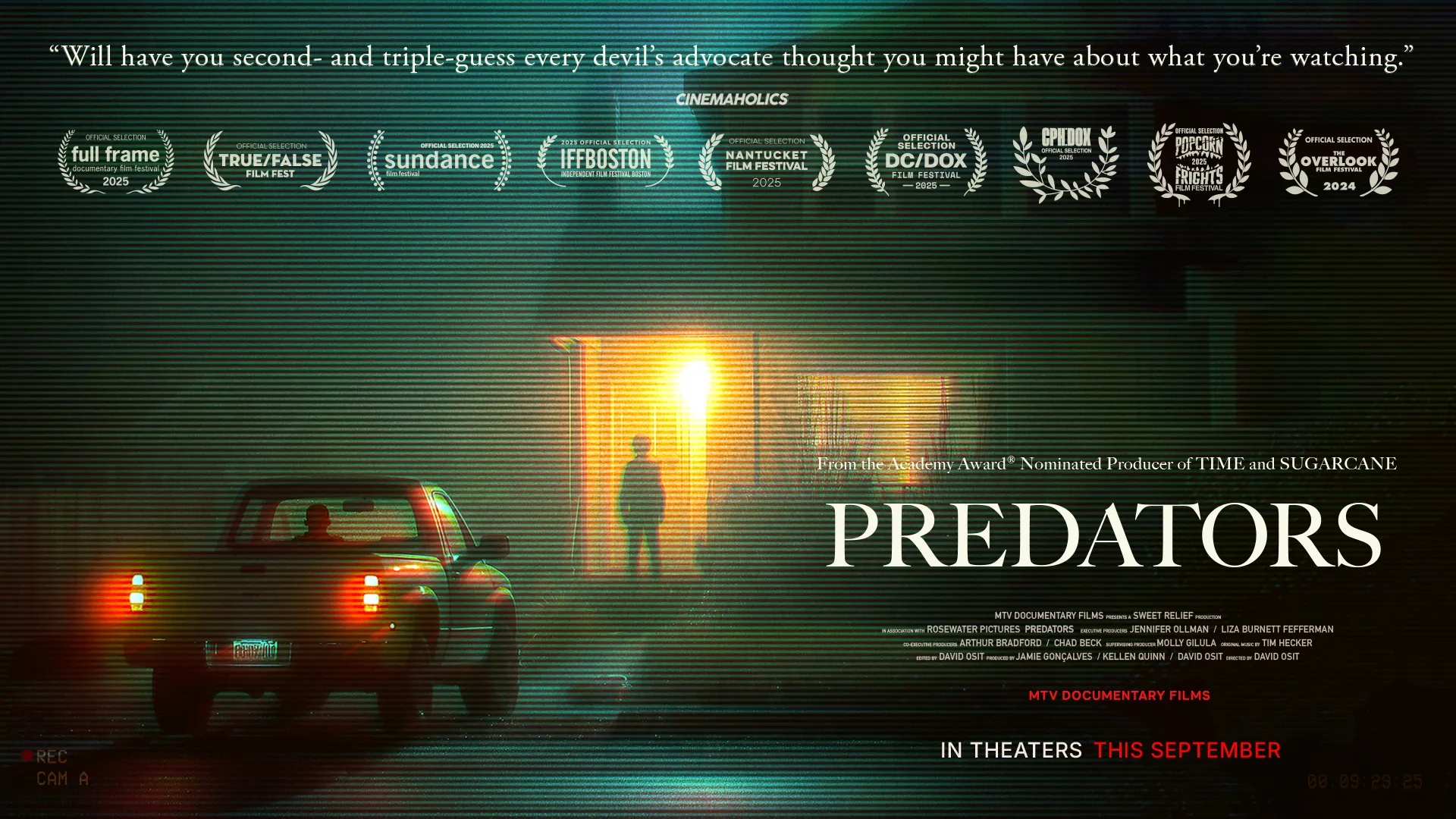

Predators (2025) (dir. David Osit)

There’s a moment early in David Osit’s documentary Predators where ethnographer Mark de Rond describes the signature scene from “To Catch a Predator”: “In that moment, time stops. What you’re seeing is effectively someone’s life end and they realize it.” It’s a chilling observation about a show that millions of Americans once watched with a mixture of horror and fascination, a program that turned the apprehension of alleged child predators into prime-time entertainment. Osit’s film isn’t interested in simply rehashing the controversy surrounding Chris Hansen’s infamous NBC program. Instead, “Predators” asks a far more uncomfortable question: What does our consumption of this content say about us especially since it exploits those engaging in criminal behavior and we the audience are finding it “entertaining?”

Predators is not an easy film to watch, nor is it meant to be. Osit, whose previous documentary “Mayor” followed a Palestinian politician navigating Israeli oppression, brings the same unflinching moral inquiry to this examination of “To Catch a Predator,” the “Dateline NBC” segment that ran from 2004 to 2007 and became a cultural phenomenon despite airing only 20 episodes. The show’s formula was simple and devastating: members of the volunteer organization Perverted-Justice would pose as minors online, lure men to a house with promises of sex, then watch as Chris Hansen emerged from the shadows with his camera crew to confront them. After tearful apologies and humiliating interrogations, the men were told they were “free to go”—only to be tackled by police waiting outside.

What makes Osit’s documentary so powerful is his access to raw, unedited footage that never made it to air as well as a personal experience to share. Through Freedom of Information Act requests and deep dives into online fan communities (yes, the show has devoted fan communities who catalog every detail), Osit obtained hours of material that reveals a far more complex and disturbing picture than NBC’s slickly edited broadcasts. In these unguarded moments, we see the alleged predators not as cartoon villains but as human beings—broken, desperate, often begging for help and therapy. “To show these men as human beings,” de Rond observes, “the show kind of breaks down.”

This is precisely Osit’s point. The film is structured in three acts, each building on the last to create an increasingly damning portrait of America’s relationship with crime, punishment, and entertainment. The first act examines the original show, featuring interviews with the young actors who played decoys. Now parents themselves, they speak candidly about the mental toll of their participation.

“There were a few, I wanted to just be like ‘go home,’” one recalls. Another, who was present during the episode that ended with Texas district attorney Bill Conradt shooting himself as the camera crew approached his house, remains visibly traumatized. The footage of Conradt’s death is devastating, made worse by police officers joking about it shortly after. One law enforcement officer describes his involvement as “a stain on my soul.”

The second act reveals that “To Catch a Predator” didn’t die—it mutated. Osit follows “Skeet Hansen,” one of many YouTube imitators who have taken the format and stripped away even the minimal oversight that NBC provided. These amateur predator hunters operate with shocking recklessness, their videos garnering more views than episodes of “Saturday Night Live.” The production values are shoddy, the legal boundaries even blurrier, and the potential for violence significantly higher. Yet millions watch, click, comment, make fun of perpetrators and share. Osit found himself deeply uncomfortable filming with Skeet at a particular moment, realizing he had become just another camera crew exploiting someone’s downfall — a transgression, a compulsion, their sickness.

The third act brings us face-to-face with Chris Hansen himself, now producing an even trashier version of his original show. In a scene that crystallizes everything wrong with the format, Hansen’s team targets an 18-year-old named Hunter who was planning to meet a 15-year-old—an age difference that wouldn’t be illegal in certain states. They proceed anyway. “I hope we’re not ruining his life,” one producer says casually over lunch. We then meet Hunter’s devastated parents. “I just don’t know how the worst day of my life could be something that people are getting snacks for,” his mother says, her words cutting through any remaining illusions about the show’s noble intentions.

Osit refuses to provide easy answers or moral certainty. He’s not defending child predators—the opening audio of a 37-year-old man speaking to what he believes is a 13-year-old is skin-crawling enough to establish the genuine horror of these crimes. But he is asking why, after 20 years of these operations, Hansen still has no idea why men commit these crimes or whether rehabilitation is possible. When Osit poses these questions to Hansen, the host admits he doesn’t know. A former Kentucky attorney general, sporting his official Dateline cap, is even more blunt: “That’s not my job to rehabilitate them or get them therapy.” He calls them “hardened criminals,” acknowledging most had no prior criminal records.

Willful ignorance is the point. As de Rond explains, the appeal of shows like “To Catch a Predator” depends on not understanding the perpetrators. Understanding would require nuance, empathy, and difficult conversations about mental health, rehabilitation, and the root causes of sexual abuse. It’s far easier—and more profitable—to simply watch unhealthy, impulsive people get destroyed. Jimmy Kimmel called it “the funniest comedy on television.” Oprah praised Hansen’s “amazing work.” Jon Stewart suggested he deserved his own channel. Hansen appeared on “30 Rock” and “The Simpsons.”

Predators forces us to confront our complicity in this vicious cycle. Osit draws uncomfortable parallels between Hansen’s work and his own, noting that both are filmmakers creating content from people’s lives and experiences. The difference, he suggests, is that he believes he’s not harming anyone—but Hansen believes that too. The film becomes a meditation on documentary ethics, true crime’s explosive popularity, and America’s preference for punishment over rehabilitation, for spectacle over understanding and compassion.

In connecting “To Catch a Predator” to broader issues—mass incarceration, the erosion of nuance in public discourse, the greediness of YouTubers, the dehumanization that allows us to dismiss groups of people—Osit has created something rare: a documentary that’s thought-provoking, personal, revelatory.

Predators arrives at a moment when America seems more divided than ever, when complexity is treated as weakness and empathy as naivety. Osit isn’t asking us to forgive the unforgivable. He’s asking us to examine why we’re so eager to watch people’s lives end (criminals or not), why we’ve turned suffering into entertainment, and what it costs us as a society when we refuse to ask difficult questions. The film is a fractured mirror, and what it reflects back is deeply unsettling. Whether we choose to look (or understand) is up to us. This is a film I definitely won’t stop thinking about for quite some time.

Mental Filmness Film Festival 2025 Wrap-Up!

Do Other People (dir. Tim Kail)

Several of the films playing this year’s festival comes courtesy of returning filmmakers with other personal, vulnerable experiments that often play like video diaries rather than a straightforward narrative. In a way, it’s like peering into the fragility of the human mind, sometimes akin to an audio-book or a podcast where the narrator is sharing their innermost feelings and apprehensions.

I last described Tim Kail’s other great film, I Was Not Who I Was as an introspective portrayal of a man experiencing intrusive thoughts, attempting to find a sense of calm during a possible mental collapse. It is better than many feature length films that tackle similar subject matter and the same holds true for his other lo-fi, low-key work here that still packs a punch beginning and ending with a knife in a drawer.

Do Other People is an intimate portrait of living with a negative voice that isn’t going anywhere, crafted with the kind of raw vulnerability that only comes from deeply personal filmmaking. Writer-director-star Tim Kail strips away any pretense in this quietly powerful video diary of sorts, creating a film that feels less like a traditional narrative and more like an honest conversation with oneself, in order to come to terms with negative energy in hopes of acceptance.

Shot in stark black and white, the film follows a young man with bipolar disorder as he navigates the daily battle against disturbing, automatic thoughts that refuse to stay buried. What makes Kail’s approach so effective is his focus on the small, contemplative moments that comprise the reality of mental health struggles—the walks, the journaling, the time spent with his dog, the meditation sessions. These aren’t dramatic crisis points but rather repetitive coping mechanisms that get someone through another day.

Kail tells his story primarily through images and close-ups rather than conversations with characters, allowing the visual language to convey the gray area between depression and the motivation to break free from melancholy’s grip. The black and white cinematography reinforces this liminal space, capturing the uncertainty of whether the darkness will prevail.

The film’s power lies in its refusal to offer easy answers. Instead, it presents intrusive thoughts as something that never really goes away—a daily cycle that requires constant management. As long as you can wake up and think, “I’m okay,” there’s hope. The knife is still there but so is the motivation to keep going.

The ending provides not triumph but relief: the simple, hard-won victory of getting through another day by talking back to your thoughts, whatever method works for you. In its DIY simplicity—Kail even stars alongside his own dog—Do Other People achieves something remarkable like a lot of films in the festival: it makes the deeply personal feel universal, proving that sometimes the quietest films speak the loudest truths about mental instability.

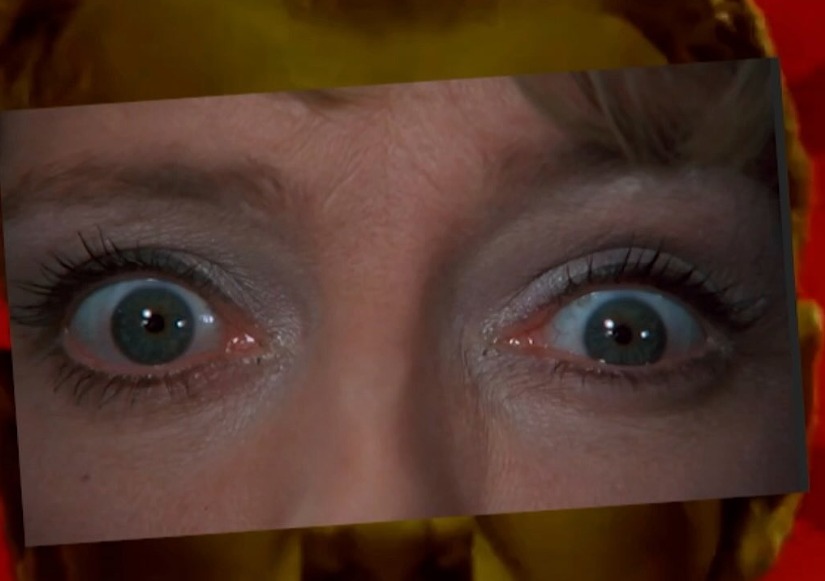

Murdergame (dir. Philip Brubaker)

A phantasmagorphic essay on the films of Alfred Hitchcock that quickly veers into controlled insanity, Philip Brubaker’s Murdergame is less a conventional film essay than a fever dream about wide-eyed obsession. What begins as an ostensible study of themes in Hitchcock’s work spirals wildly off the rails into surreal imagery—physical video filmstrips attacking the filmmaker, Tetris blocks descending into chaos—creating something that defies easy categorization. I can’t say that I loved it in the same way I did his previous work, How to Explain Your Mental Illness to Stanley Kubrick, but I was certainly amazed watching a madcap mosaic unfold before my eyes. As much as I thought “what the hell am I watching,” I was also grateful that it was created at all.

This is experimental filmmaking at its most unhinged and personal. Part of Brubaker’s “Trilogy of Delusion,” Murdergame doesn’t attempt to literally portray a manic episode; instead, it evokes the visceral feeling of one, channeling what Philip describes as “the unhinged freedom of magical manic thinking.”

Murdergame dares to dice and slice all expectations, coming across less like traditional filmmaking and more like a Pollock painting projected onto the screen. It’s confusing but deliberately so. You’re put inside the manic mindset of someone trying to make sense out fractured experiences, like peeking into a kaleidoscope, unable to detect a precise consistency in the imagery. You’re following Brubaker’s thought patterns through visuals that likely may not make sense to even himself at times.

As I recently stated in a review about Jodorowsky’s work: “movies can be whatever they want to be and there’s nothing you can do to stop them.” Murdergame embraces that philosophy completely, offering a boldly original work that expands our understanding of what constitutes a video essay/experiment. It’s weird, it’s bold, it’s utterly unlike anything else you’ll see.

Don’t Fail (dir. Hayley Nash)

Never am I more aware of germs and sanitizer than when I visit the gym. There are alcohol wipes, towels, reminders to wipe down the equipment everywhere. So I can imagine what someone with OCD might experience having to lift weights competitively every day.

Following a female weightlifter grappling with obsessive-compulsive disorder during competition, Don’t Fail communicates its protagonist’s internal struggle through potent cinematic language—repetitive actions, oppressive yet muted lighting, and an anxiety-inducing sound design that buzzes with mounting tension. There’s a memorable scene involving our lead character Mia (Cristal Bella Romano) confronting her mother where the score does the um, heavy lifting, but it accentuates the emotion rather than bludgeoning the audience.

Nash, drawing from her own experience with both competitive weightlifting and OCD, brings a raw, realness to the material that elevates it beyond a typical dramatic short. She understands that weightlifting is inherently about repetition—lift, repeat, again, again—and uses this structural reality to mirror the monotonous loops of OCD. Nash explores how the pressure to achieve perfection in athletics and academics can exacerbate mental health struggles, while also touching on the importance of grounding oneself in the face of pressure and knowing when to step away.

The result is sometimes uncomfortable but riveting—a portrait of someone caught between the drive to succeed and the mental traps that threaten to derail them. Fans of Lauren Hadaway’s The Novice will recognize the territory: athletic determination colliding with psychological instability, rendered with unflinching intensity. Nash’s film is a powerful reminder that the battles we fight in our own minds can be just as demanding as any physical competition.

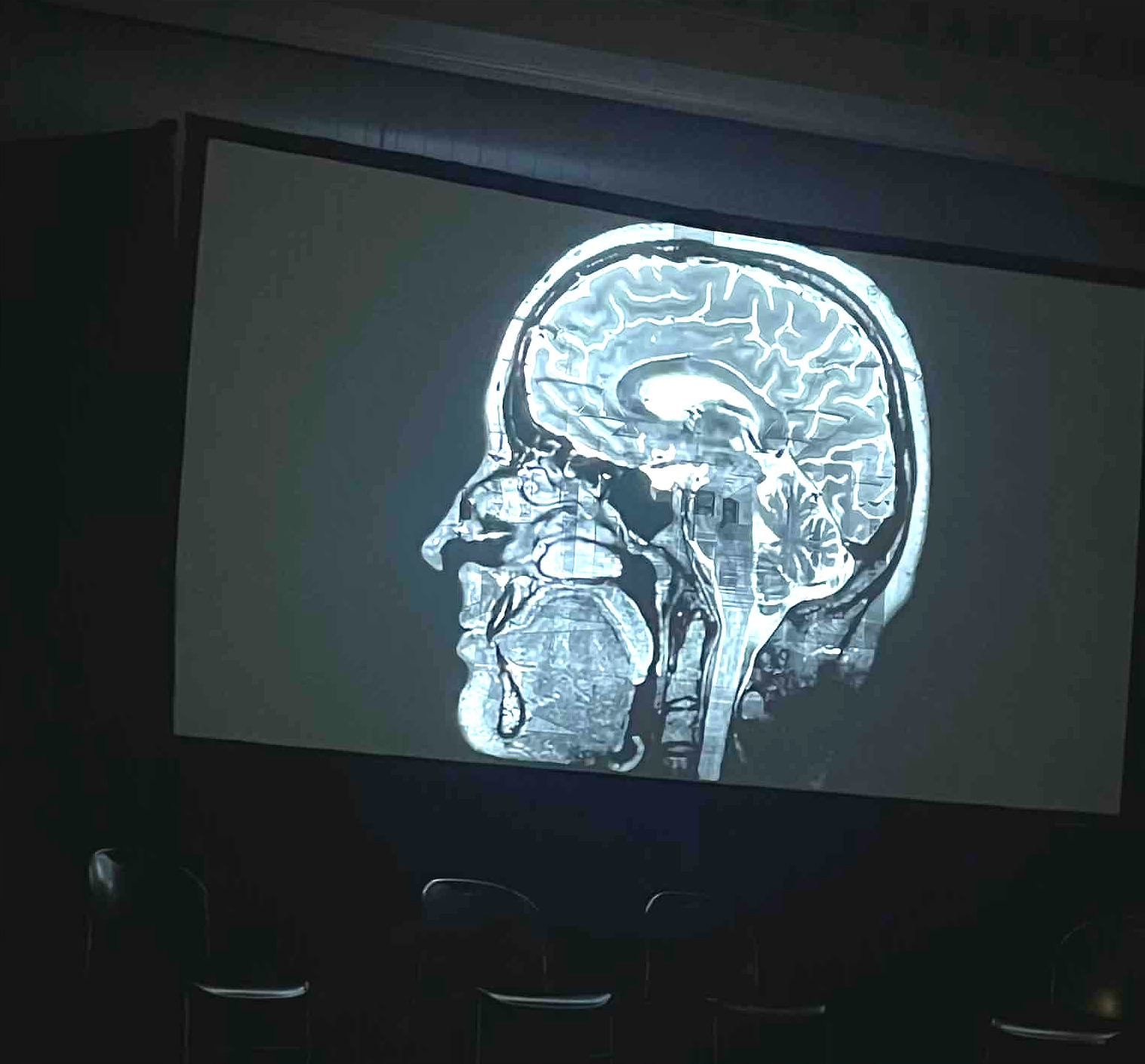

Head War (dir. Sadie McCarney)

Poet/essayist Sadie McCarney’s experimental half-hour short is a disorienting memoir, a deep dive into the mind during a psychiatric crisis. The text version of Head War won the 2021 Oscar Wilde Award for Work Celebrating Non-Conformity at the Island Fringe Festival. Drawing from found text in her own mental health records from a two-month inpatient stay in 2013, McCarney crafts a tone-poem that captures the manic chaos of her experience with startling authenticity. The title perfectly encapsulates its central tension: a tug-of-war between delusions of grandeur—believing herself to be Joan of Arc and head of Google’s operations—and emerging clarity needed to secure her release.

What makes Head War distinctive is its refusal to sanitize or dramatize psychiatric experience in conventional ways. McCarney performs alone against sparse backdrops—bus doorways, empty office rooms—addressing nonexistent audiences while a search-engine voice narrates her fractured thoughts. The absence of other voices amplifies the isolation and internal battle at the film’s core. It’s rough-edged, idiosyncratic, and deliberately uncomfortable viewing, but therein lies its power. The free-associative structure mirrors the experience it depicts, even when certain tangents feel disconnected. Not every thing works (including a sequence revolving around urine) but the audacity and rawness is what makes this approach consistently interesting to watch.

While not always cohesive, Head War succeeds where polished psychiatric dramas often fail: it feels true to its creator. McCarney’s wild imagination and dark humor create something more honest than pleasant—a manic wildcard energy that refuses to be tamed into easy narrative or false hope.

My Memories (dir. Alvaro Garcia)

Of all the films playing Mental Filmness this year (and there are several others I enjoyed like Forever Dying, Dreamscapes, Quiet Arlo, Crowboy, Common Law) the one that moved me the most is only 7 minutes long, but of course, since it reminded me of the work of Charlie Kaufman, it gets my vote for the best.

My Memories is a profound sci-fi meditation on memory, identity, and aging that accomplishes more in five minutes than many features manage in two hours. The premise is deceptively simple: an elderly man’s daughter attempts to retrieve his digitized memories from a corporate service, only to discover they’ve been given the “wrong” ones. But as these unfamiliar images flicker across the screen and her father is unexpectedly moved, the film poses a deeply human question: if memories touch us, do they belong to us—does accuracy even matter?

Garcia’s film works both as gentle satire of our increasingly digitized lives and as a tender exploration of dementia and the fallibility of memory itself. The science fiction framework—a world where tech giants store and commodify our most intimate moments—feels uncomfortably plausible, yet the film never loses sight of its emotional core. Beautifully shot and acted, it captures something essential about how memory reconstructs rather than reflects the past, how our recollections shift and change based on experience and perception.

What makes My Memories particularly moving is its compassionate stance toward cognitive decline. Rather than treating forgotten memories as tragedy, the film suggests that perhaps what matters most is the smile in the face of demise—whether triggered by accurate memories or not. It’s a quietly radical reframing of how we think about aging and remembrance, one that offers comfort rather than despair. In an era where we outsource our memories to algorithms and cloud storage, Garcia reminds us that the value of a memory lies not in its precision or accuracy, but in its power for the emotion to stay with us.

Congrats to Sharon Gissy and all the filmmakers on another incredible lineup of Mental Filmness. Be sure to catch the virtual fest here! See you all in 2026!