The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) (dir. Tobe Hooper)

Kim Henkel, when asked why he created the ‘chainsaw family,’ replied with a smile that he ‘wanted to scare the shit out of someone.’ Tobe Hooper has said that, ‘I think what I was trying to say was: This is America!’

I’ve been thinking about my father since it’s been 24 years since he passed almost to the day. I also have moments where I ask, “why am I writing? why am I podcasting? why do I continue to love film?” I think a lot of it has to do with trying to comprehend the person I was closest with and is no longer here. Part of me can’t help but wonder, how did my dad process The Vietnam War especially since he was in the Navy. That’s a whole other story I’ll never uncover from him.

Suffice to say, when I read the work of Joan Didion or revisit films from the early 70s, there is a tendency to place my thoughts within a context of wonder. One of the people responsible for putting me on this planet had this other life before I was born. Is this my way of tapping into his spirit, his memories? I often think of even just the simple needle drop in Inherent Vice of “Journey Through the Past” as making me cry only because it’s hard not to think of my dad’s love of Neil Young, but also, what was his life like during the hippie era right into when Nixon took office. There’s so much to unpack which is why a lot of writers, artists, and filmmakers keep going back to understand the death of the 1960s.

Now there is a whole other reason to protest currently in this country. But let’s steer clear of that correlation for the time being. But the idea of “othering” and ostracizing those who don’t fit a certain standard or class system isn’t going anywhere. We’re stuck in this endless cycle. We escape momentarily and possibly even laugh once we find our way away from the threat, but there are still “Leatherfaces” out there in the world, dancing with dismay holding their weapon of choice waiting to unleash upon those who dare to disrupt their lives. Sally may have escaped but it’s not over for her. It’s not over for any of us. Even though the loss of my father is now going on two and a half decades, the pain of losing him is still here but this is also my way of taking that grief and turning into something else entirely: an analysis of my favorite horror film ever made.

When Tobe Hooper stood in a crowded Montgomery Ward hardware department during the 1972 Christmas shopping season, fantasizing about carving his way through the consumer masses with a chainsaw, he unwittingly channeled the rage, fear, and disillusionment of an entire generation. The resulting film, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), would become far more than a horror movie—it emerged as a visceral document of post-Vietnam America, a nation cannibalizing itself while its citizens stumbled blindly toward slaughter. Drafted soldiers became strangers in a strange land, going where they weren’t wanted.

At the heart of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre lies a disturbing inversion of the American social contract. The film’s cannibalistic family, former slaughterhouse workers displaced by industrial automation, have simply redirected their skills toward new prey. As the hitchhiker explains with unsettling matter-of-factness, his family has “always been in meat.” When the local slaughterhouse introduced new technology and put people out of work, these laborers didn’t abandon their trade—they changed their product line from cattle, pigs, chickens to humans.

This transformation speaks to a profound class critique embedded in the film’s DNA. The Sawyer family represents the working class broken not just by poverty, but by the dehumanizing nature of their labor as brought upon a fractured system of power. Make people do inhumane work, and their humanity erodes. Then take away even that brutal employment, and they must scratch out survival by any means necessary.

The film suggests that industrial capitalism doesn’t just exploit workers—it fundamentally transforms them, stripping away the qualities that separate human from animal, predator from prey. They no longer see a woman screaming for help, they only see “meat.” No one wants to think that any one is capable of this kind of horrific behavior, but Ed Gein certainly became the psychotic result of more than just a domineering mother, he too was unable to adapt to the outside world in any healthy manner.

The young travelers who stumble into this nightmare occupy the opposite end of America’s class spectrum. Sally Hardesty and her companions are clearly educated, mobile, leisured. Their grandfather owned the very slaughterhouse that once employed the cannibal family. This detail, easily overlooked, provides the film’s most chilling irony: the victims are being consumed by the human machinery their own class created. The Hardestys benefited from an industry that treated living beings as flesh, now that same logic has turned upon them.

Throughout the film, the young people are systematically reduced to the status of livestock. Pam is literally hung on a meat hook. Kirk receives the same swift, brutal dispatch as a steer—a hammer blow to the skull, his body twitching and convulsing exactly like a slaughtered animal. The mechanical sounds that dominate the film’s soundscape—generators, chainsaws, the metallic clang of tools—create an auditory landscape of industrial slaughter. Even the squealing pigs heard throughout aren’t just atmospheric; they’re a constant reminder of what these young people have become in Leatherface’s eyes: meat on the hoof.

This reduction of humans to animals operates on multiple levels. The film suggests that modern industrial society has created a system where people are already treated as livestock—processed, commodified, and consumed by forces beyond their control. The Sawyer family simply makes this metaphor literal. They are the logical endpoint of a society that has always valued profit over people, efficiency over humanity.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre premiered in October 1974, as America was still reeling from the Vietnam War’s conclusion and the metastasizing Watergate scandal. The film’s production period, from early 1973 through 1974, coincided almost exactly with Nixon’s downfall—from his “peace with honor” speech in January 1973 to his resignation in August 1974. This timing was not coincidental; it was essential to the film’s meaning.

The Vietnam War had shattered the consensus that positioned America as a force for good in the world. Young men—some as young as sixteen—were drafted and sent to die in a conflict whose purpose grew increasingly murky. The war didn’t just kill soldiers; it killed faith in American institutions, in the government’s honesty, in the very idea of national purpose. Those who are supposed to protect us from harm, were now callously trying to transform men into killing machines. When those who survived returned home, many found themselves mentally broken, unable to reintegrate into a society that had sent them to commit and witness atrocities (which is likely happening with Sally once she finally gets home, safely).

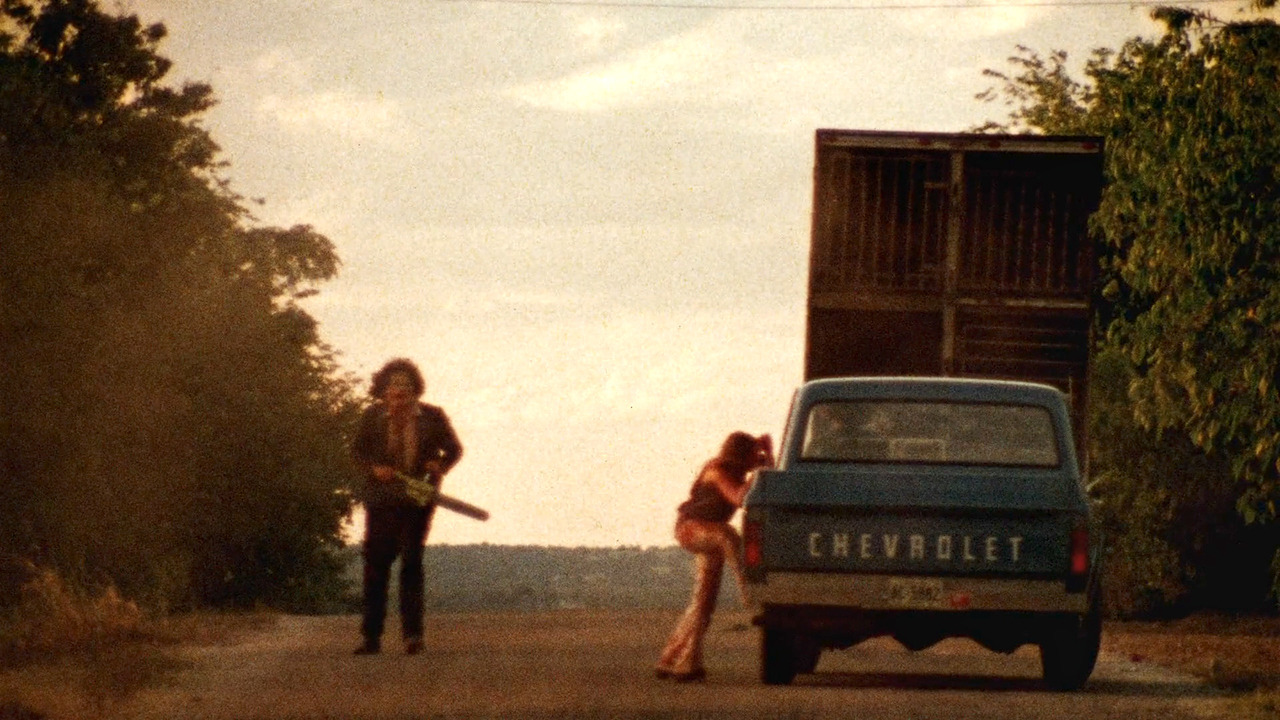

Sally’s escape at the film’s conclusion—covered in blood, laughing maniacally in the back of a pickup truck—mirrors the experience of Vietnam veterans. Yes, she survived. But survival isn’t the same as salvation or escape. Her laughter, cutting between shots of Leatherface waving his chainsaw in impotent rage, suggests irreparable psychological damage on both a personal level and a national one. She has escaped one horror only to face another: living with what she’s experienced. The film refuses the comfort of a traditional happy ending because America in 1974 had no happy ending to offer.

The film’s relentless assault on the senses—the oppressive heat, the mechanical drone of chainsaws and generators, the unending screams and impeccable soundscapes—recreates the overwhelming sensory experience of combat. The score, in particular, functions as a sonic bombardment that mirrors the merciless fear Americans felt as their government drafted young people and “picked them off one by one,” as one critic observed. The film doesn’t let viewers rest, doesn’t provide the traditional horror rhythm of tension-release-tension. Instead, it maintains a constant state of assault, much like the war itself.

Even the film’s visual strategy speaks to Vietnam-era anxieties. The contrast between the sunny, optimistic outdoor scenes and the dark, decaying interior of the Sawyer house suggests the gap between the America people were “sold” and the America that actually existed. The government had promised a quick, righteous war; it delivered a quagmire. It promised prosperity; it delivered economic crisis. The bright Texas sunshine becomes a cruel joke, illuminating a landscape of death and betrayal. The sunshine contrasted with the display of corpses bathing in light, recalls the work of Frances Bacon. It’s ugly, it’s beautiful, it’s everything that the film is conveying right at the very start.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre embraces a brutal dichotomy and fragmentation deliberately. Consider the cemetery sequence where Sally walks to inquire about her grandfather’s grave. The camera remains at extreme distance, using the wide shot to isolate her small figure against the sprawling landscape of tombstones and monuments. This framing choice refuses the viewer intimacy or clarity, instead emphasizing disorientation and vulnerability. We watch Sally navigate the cemetery as if observing from afar, unable to protect her or even fully perceive what threatens her—a visual strategy that mirrors the film’s broader refusal to offer comfort or coherent explanation.

One thing Tobe Hooper refused to do in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was to give us the relief of a resolution. Sally, the last hippie standing, loses her boyfriend, her brother, and her friends and escapes death herself only by the grace of the timely intervention of a passing driver. The Sawyers (with one exception) aren’t vanquished. As Sally flees in the bed of a pickup truck, hysterical and soaked in blood, Leatherface dances with his chain saw, an expression of frustration at losing his quarry, but also the reaction of someone who won’t be punished or held to account. The danger is still there, waiting for the next vanload of unsuspecting travelers. Sally may have won the battle, but the threat hasn’t diminished; we haven’t even begun to grapple with its causes. America’s story is still ongoing. Things will get better, and worse, and better, sometimes by turns and sometimes all at once. The most hopeful part of Hooper’s American masterpiece? Sally doesn’t get through her ordeal unscathed. But she does get through it - Emily C. Hughes - Slate Magazine

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre remains one of the most important and misunderstood films in American cinema. Often dismissed as exploitation or lumped together with the wave of “slasher” films it would inadvertently inspire, Hooper’s masterpiece deserves recognition as something far more significant: a profound work of art that captured the messy, terrifying mood of a decade and transformed it into a nightmare from which there is no awakening.

Now it hits home again given the horrific political climate we are faced with. This is not a film about a monster hiding in the shadows—it’s about what happens when an entire society becomes monstrous, when the machinery of civilization breaks down, and when human beings are oppressed, captured, tortured, victimized. Some things never change.