We Can't Go Home Again (1973) (dir. Nicholas Ray)

We’re often losing ourselves inside the noise of society but an expression through art is an act of trying to find our way back to common humanity. Watching the very last film by one of my favorite directors, Nicholas Ray, in an attempt to keep warm with below zero wind chills outside, I couldn’t help but feel euphoric in what he achieved as a final statement. But let me state up front: it’s fucking weird and difficult. Not to mention, it was filmed during another politically challenging period in which many were feeling hopeless. “We may be through with the past, but the past is never through with us.”

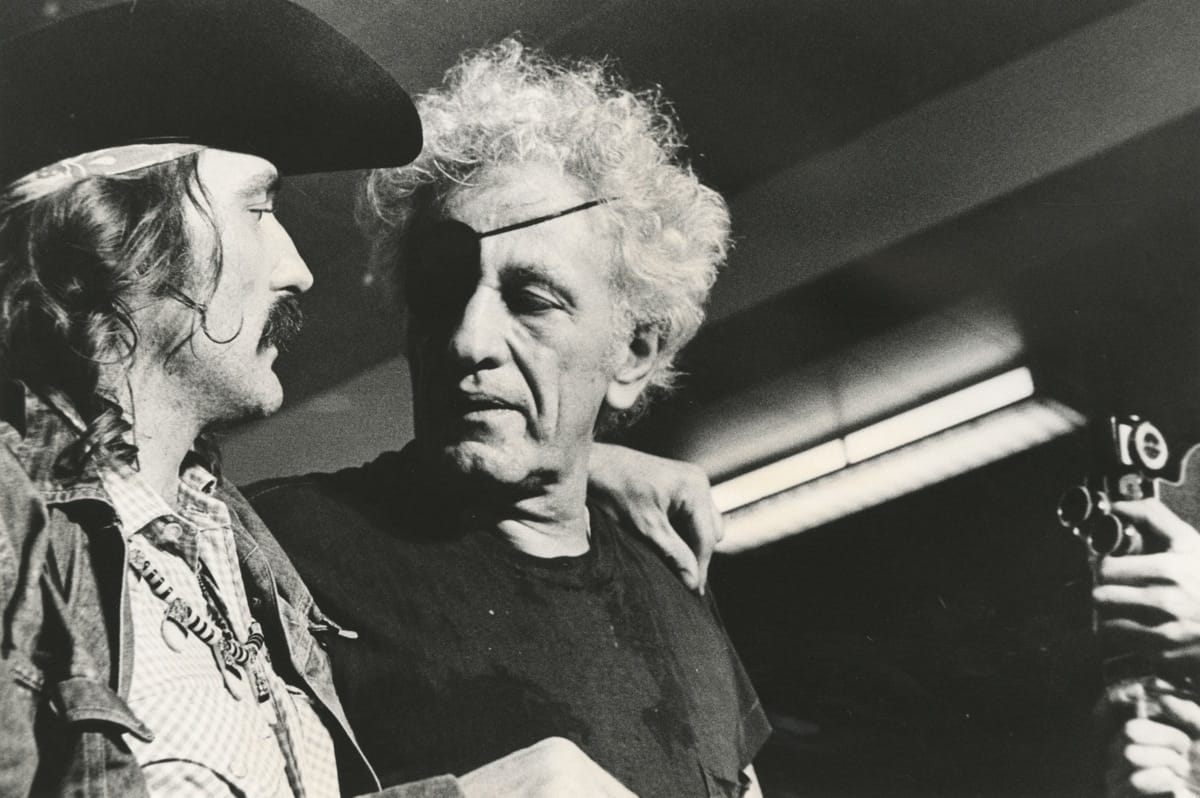

Nicholas Ray was through with Hollywood after two impersonal epics in a row with King of Kings and especially 55 Days of Peking in the early 60s, which he didn’t even finish due to having so many conflicts with the cast and studio alike. He then decided to teach at Harper College in upstate NY and several years later, embarked on an avant-garde project that involved writing scenes with those who wanted to learn from him. Ray didn’t like lecturing at all, he wanted to teach at night, actually making a film side by side with young, eager students. At the same time, he also wanted to make something unexpected, personal and autobiographical.

When you look at, We Can’t Go Home Again, the first thing that sticks is this chaotic, fragmented, almost overwhelming visual language. It’s not just a break from convention; it’s a full-on dismantling of it. You’re thrown into this kaleidoscopic nightmare of layered images, distorted colors, overlapping scenes. It’s as if Nicholas Ray said, “Let’s destroy the frame and see what happens.”

The multi-dynamic imagery—yeah, I guess I’ll call it that—is like broken glass, with shards flying in every direction. “Look out,” he seems to say. “You might get cut.” There’s Super 8mm and 16mm footage playing next to each other, sometimes duking it out for attention, other times aligning for just a second before shattering again. Wim Wenders and Walter Murch, both declared it a “mess,” and they aren’t wrong. It’s audacious in its messiness.

There’s both audio and video manipulation—colors exaggerated, frames within frames, distorted into this jumbled swirl at times recalling the mad brilliance of Don Herzfeldt’s It’s Such a Beautiful Day. It feels like you’re a part of the unraveling with someone intimate, as they grapple with both personal demons and cultural chaos. Humanity is caving in on itself and Ray sensed it right from the start when introduces us to what happened to him during the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

Ray took every imperfection, every twisted glitch, and turned it up to eleven. Possibly while under the influence of alcohol and various substances that he struggled to quit. People were worried about him and for good reason. It was until the late 70s that he finally sought help for his addiction issues. But before then, he went for broke here. Images are akin to scribbles or drawings in a journal rather than fully formed sentences. The raw cuts, the out-of-sync audio, mixed with home video? He believed cinema shouldn’t just reflect life; it should embody it.

It’s more a failed film about Ray than one about his students (or about “US,” as an opening title puts it). Don’t Expect Too Much is lucid about some of the reasons for this failure, including Ray’s addictions to alcohol and drugs, but We Can’t Go Home Again is more evasive. The former opens with Ray quoting and imitating a harangue of Abbie Hoffman to art students: “What is art? Fuck art! Art is what you’re doing. Art is politics. Art teaches living,” to which Ray adds, in his own voice, “Politics is living.” But this notion — which echoes the ethics and aesthetics of action painting in the 1950s, as theorized by Harold Rosenberg — prompted Mary McCarthy to object, “You can’t hang an event on a wall.” This raises the theoretical question of whether you can project an event (as opposed to the shadow of an event) on a wall, either — or, for that matter, download or watch the same event on a computer or a mobile.

Ray stages his own death twice — first as Santa Claus hit by a car, then as himself, a suicide by hanging (which he begins abjectly and ends involuntarily, like the suicide of Godard’s Pierrot le fou). The only lesson arising from this is self-loathing and affection for his young collaborators: “Take care of each other — all the rest is vanity — and let the rest of us swing.” Bitter Victory also expressed self-hatred (along with vanity), but with a devastating critique of the macho posturing of both its heroes. Here the pain, most of it self-inflicted — Tom Farrell’s while shaving off his beard, the angry masochism of Leslie Levinson (another student), Ray’s while dying twice — is devoid of self-reflection or analysis. Once politics becomes confused with psychoanalysis, neither can function with much purpose - Jonathan Rosenbaum

Emotions, let’s be honest, are messy, noisy, and unpredictable. They can’t live inside a box. If thoughts and fears are kept inside of there, artists like Ray have an instinct to break open that box and see what comes out. Nothing about human feeling seems sanitized or smoothed over. We Can’t Go Home Again is undisciplined, chaotic (this word comes to mind a lot while watching), also admittedly pretentious and often quite impenetrable. And yet, I loved this piñata of an experiment. Mileage will vary. It helps to be a fan.

You might feel uncomfortable watching it because it defies clarity, but that’s exactly what Ray was seeking out. A truth that can only come from disorder and curiosity. Those layers, the competing visuals—they mirror the fractured psyche of not just an individual, but an entire nation on the brink. This was the Nixon era, post-Vietnam fallout, Watergate looming large.

The film, intentionally or otherwise, encapsulates that feeling of being completely untethered, like the very foundations you thought were stable have crumbled beneath your feet. Isn't that what America still feels like to this day? Again, an unraveling of humanity told with bleak, unrelenting visual punches to the gut. A broken human spirit needs help, healing and compassionate attention.

We Can’t Go Home Again is a kinetic, psychedelic ode to disillusionment. If the 1960s were about revolution and idealism, then the early 70s were about reckoning with the fallout—Vietnam, Watergate, the unraveling of counterculture. At this juncture, Nicholas Ray turned his lens on a lost generation, and let me tell you, it wasn’t exactly a flattering close-up. His students, the ‘post-68’ youth, weren’t storming barricades anymore. Instead, they were manifesting something to replace a crumbling sense of purpose. Ray captured this shift with a brutal audacity to defy what cinema could be.

The commune he and his students built wasn’t just a filmmaking experiment. At times, it reminded me of what Brian De Palma did with Keith Gordon and company when they collaborated on Home Movies. Both teacher and student took risks to a dizzying degree. Joel Potrykus is a more recent example of a daring storyteller who often chooses to collaborate on short films with many film students attending his filmmaking class at Grand Valley State University.

The best way to learn is to be a part of the process instead of simply just being taught. Ray may have been older and experienced, as his students point out, but they have a lot to learn despite wanting to “do their own thing.” I couldn’t help but laugh out loud at a student’s review of Rebel Without a Cause, stating directly to Professor Ray, “it was okay.”

This wild, wild endeavor ended up becoming a metaphor for the fractured idea of “home”—that yearning for a place of safety and belonging, but also the realization that such places might not exist anymore. Sometimes we want to recapture the feeling of our youth, but we can also never go back.

You feel it in every frame: the tension between connection and isolation, between hope and cynicism. It captures what was happening in that specific time and place. These ambitious young adults perform their real-life psychodramas via Bolex cameras, peeling back layers of themselves as Ray guides them—sometimes tender, sometimes cutting, always raw.

Ray delved into his actors’ psyches like a conductor pulling melodies from clashing instruments. His method was, in a word, personal. Scenes weren’t just blocked; they were sculpted out of emotion, sometimes improvised, often re-enacted from real moments of pain or revelation. Take the sequence where a student emotionally recounts her strained relationship with her father—it’s heart-wrenching because it’s not a performance. It’s lived truth, pushed through Ray’s lens and layered with his almost invasive intensity.

An unorthodox production of Ray’s design may have initially started as a form of therapy and reflection, but the final version represents cinema as confrontation. Then there’s the ending—or, really, a crescendo. Ray stages his own suicide in a barn—a professor, a filmmaker, a man consumed by his own visions. His final words, “Take care of each other,” aren’t just a plea. They’re a challenge, a reminder, a call to find unity amidst the chaos.

Again, it feels relevant given what we’re all about to face once again in this country. But it’s also deeply, achingly sincere to watch a maverick like Ray be that direct. It leaves you questioning: What do we owe each other, especially when the foundations—family, country, even oneself—begin to erode?

Ray was 60 when he began crafting, We Can’t Go Home Again. It was a full-throated experiment, a leap of faith, and honestly, a bit of a middle finger to the comforts of traditional cinema conventions. His final thesis is almost a plea for others to throw caution to the wind even if others will inevitably struggle to connect to this exercise.

Nick knew the problems with We Can’t Go Home Again, both structural and technical. I’m pretty sure no one knew them better. As a filmmaker and as a teacher, he despaired over them, as he did over what he saw of himself onscreen. At best it’s a major challenge to find oneself a subject of one’s own work; and this was not Nick was at his best. The tragedy of the film, if there is one, is that eventually he did pull himself out of addiction; he did redeem himself and find a clarity with which he could have finished the film. He just didn’t get the time.

We Can’t Go Home Again is messy, flawed, and unfinished, at times infuriatingly so. But the mess, like the dirt of this Earth, is fertile, teeming with life and potential. And I can’t help but think that the life of it lies precisely in its mess and imperfection, in the profound humanness of it; and that this life in it is its greatness. A good artist makes a work of art, as polished, complete, and perfect as it can be. A great artist conspires with God to make life, which, as it turns out, is anything but - Susan Ray

It’s as though Ray took every piece of himself—all the turmoil, the brilliance, the mistakes—and poured it onto this anarchic palette. It’s raw, it’s chaotic, and for those willing to meet it halfway, it’s downright exhilarating. You watch it and think, why do movies always have to be neat, tidy, easily digestible when they can exist in this unsafe space. As Michael Keaton in Batman proclaims, “You wanna get nuts?! Come on, let’s get nuts!” That should be a message to all filmmakers now more than ever.

Picture this: you’re thrown between images of the 1968 Democratic National Convention and a close-up of a young man literally cutting away his own exterior—shaving a beard that’s become part armor, part burden. Or how about the students living together deciding to have cauliflower and ice cream for dinner. There is laughter to be found among the unrest and Ray does have a sense of humor, albeit a dark, sardonic one.

These moments are exactly what Ray was going for—an endurance test for the audience, yes, but also a declaration. To him, truth was far too complex to fit into a single, cohesive narrative. For me, it feels like watching a Jackson Pollock painting come to life—a disarray of thoughts, images, and emotions swirling together in a fragmented, stream-of-consciousness experience.

Why can’t cinema be messy and challenging, like life itself? Why can’t it knock you off balance, like those moments where the personal collides with the political, where past dreams dissolve and give way to something rougher, more real? It’s confrontational, not in a way that alienates you, though, but in a way that demands your intellectual and emotional engagement.

I’ve felt that about the majority of Ray’s work starting with my absolute favorite of his, They Live by Night. Then take a look at something like In a Lonely Place, Johnny Guitar and Bigger Than Life and you’ll see that Ray was not a work-for-hire in most cases. The cinematography alone in both of those films really is transcendent to the point where I made an effort to see them on a big screen.

Ray always wanted to challenge the audience. Nearly every film he made felt like a passion project that was homed in on the inconsistent psychology of human nature. He also had such energy behind the camera that never dissipated until he told stories that were less personal. That’s when he left it all behind. I’ve loved so many of his films that I imagine I’ll be writing about more in the future for sure.

His final opus, We Can’t Go Home Again is jarring, sure, and it catches you off guard in ways that regular movies just don’t. It’s haunting, splintered and yet, there’s beauty in those fractures. Ray turns madness into meaning, and to do so in his final cinematic effort, at the end of his life no less crafting a personal memoir that jumps around in thought. Nicholas Ray could’ve easily chosen a safer path. He could’ve stuck to formulaic storytelling, made something that audiences could easily access.

Instead, he pulled the rug right out from under us and proved that cinema can be anything: a howl, a confession, even a raw nerve or an open wound on screen. Like the majority of his work, it is a challenging portrayal of characters going their own way, learning how to navigate impulsive instincts all while making sense of various volumes of complicated human drama. All the while, he reminds us to embrace the imperfect, the struggle, the unexpected, in art—and in life.